Today’s post is totally G-rated, and promises to be the cleanest writing I’ve ever done. Bahaha! #soapjokes #yourewelcome

I stopped using mass-produced liquid body wash years ago (it’s full of toxic ingredients that are scientifically linked to immunotoxicity, allergies, cancer, and more. Thumbs down.). Hubs likes the liquid castile soap, but I’ve always found the magic of a simple, lathering bar of soap to be quite therapeutic.

As much as I’ve loved it, the humble bar of soap has always been a bit of a mystery to me.

I didn’t know how to really interpret the ingredients, I knew nothing about the soap-making process, and most of all – I had no sweet clue whether or not it was worth my money to buy hand-crafted “natural” soap rather than a simple bar of Dove or Dial or whatever was cheapest at the grocery store.

Thankfully, I was able to partner once again with one of my favourite companies, Taproot Farms Co. (the same company that changed my life by leading me to quit using coconut oil as a skin moisturizer, an article I wrote several years ago which went on to become my most popular post of all time) to share the low-down on soap with you.

This post is part of our Natural Skincare series, and is post number two. Post one was What Are Natural Skincare Products (And How Do You Spot Imposters?). In that post, I was able to glean a ton of fascinating information from the company owner to share with you, and I am doing the same thing today.

Ricky, the Taproot Farms Co. soap maker, gave me a TON of amazing info on the science of soap. I’m totally geeking out by the detailed explanations and how they make so much sense.

(Facts and explanations below are from Ricky the soap-maker, edited by me for clarity and brevity. Enjoy!)

So, what are we talking about when we say “soap”?

Scientifically-speaking, soap is a salt that results from mixing an alkali with a triglyceride or fat. Pretty simple. We mix NaOH (sodium hydroxide) or KOH (potassium hydroxide) with a liquid, pour that solution into fats/oils and end up with a beautiful bar of bubbly soap.

It seems simple enough, but when you take a closer look, there are several things that happen in that big murky pot of greasy fat and skin-stripping lye. Let’s go over the chemistry basics first, then talk about how various types of bar soap compare to one another, and finish with the advantages of the cold-process soap (what we make).

Basic soap-making methods

Cold Process – When someone refers to Grandma’s homemade lye soap, this is the process she would have used. Fats and oils are heated to make a liquid blend. A lye solution is added to the fats and no additional heat is applied during the mixing and saponification process. The block of soap firms up after a day or two and it is cut into individual bars. It is safe to use after a few days, but is soft and contains excess moisture. The soap is left to dry, or cure, for up to 6 weeks. The additional drying allows water to evaporate resulting in a proper bar of soap.

Hot Process – Similar basic formulation as the cold process except after mixing the lye solution with the fats, heat is applied. This accelerates the saponification reaction and evaporates a majority of the excess moisture. A hot processed bar of soap could be ready for market in days instead of the 3 to 6 weeks required for cold process soap.

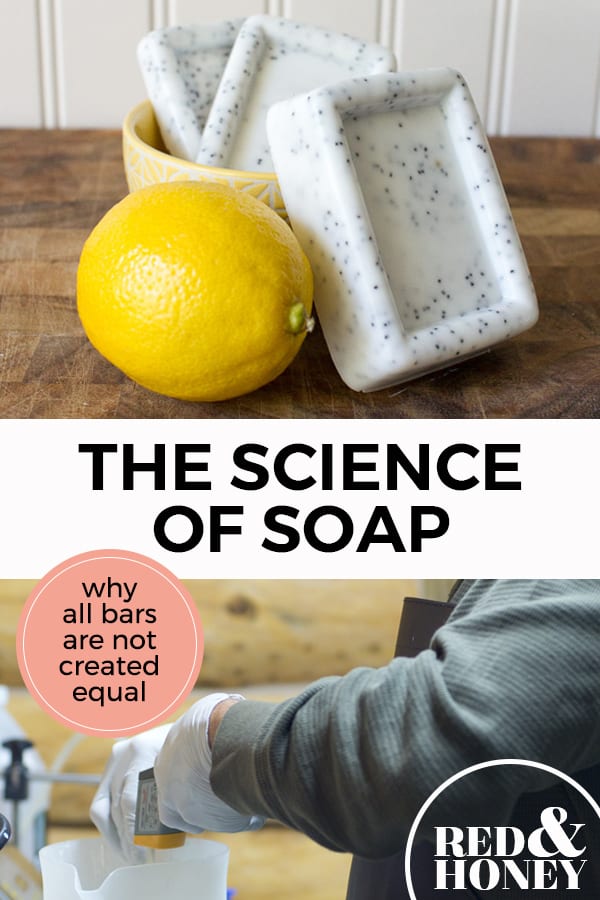

Crafter “Glycerin” Soap – This soap typically is constructed from a pre-made soap base that you can just melt and pour. It looks pretty, and is easy for the soap maker but contains much more than the simple ingredients you find in cold or hot processed soap. If soap is clear or opaque, it is probably a melt and pour.

The Basic Process

To make bar soap, we follow these basic steps:

- Mix an alkali (lye) with liquid (water or milk) in one container and place the selected fats in another container.

- Stabilize the temperatures of both the fat and the lye solution.

- Pour our alkali solution into the fats.

Variations Depend on Soap-Maker

Now, as simple as it is, the soap maker can influence the outcome (for better or worse) in a variety of ways.

For example, mixing the lye solution with the fats/oils at too high of a temperatures can result in cracked soap and other anomalies. A high percentage of liquid in the lye solution will mean a longer cure time. Too little liquid and the bar gets crumbly. A very high percentage of certain oils like sunflower or rice bran and the bar can be mushy. Too much coconut oil and it is hard as a rock.

The soap maker can also shape the characteristics of soap by varying the types of fats/oils and the amount of each, tweaking how hard, soft, slippery, bubbly, cleansing, creamy, or conditioning the end result will be.

Note: Cleansing action can be a good thing as well as bad. This characteristic indicates a feeling equivalent to how much dirt and oil is being lifted. We want cleansing but not too much. (We don’t want to strip the skin’s natural oils.)

Before we get away from our little chemistry lesson, let’s look a little closer at the very important triglyceride.

The Importance of Glycerin

As we, know the fatty acid composition of different fats/oils can make a difference to the outcome of the bar of soap. We also note that when the lye solution is added to the fats, the triglyceride separates into fatty acids and glycerin. This fatty acid/glycerin component is critical in our “old fashioned” soap making.

From one triglyceride, we get three fatty acid molecules and one glycerin molecule. Glycerin is very important to the success of our simple soap.

Glycerin is a humectant. It works by attracting and holding moisture in the outer layer of skin where dryness typically occurs. Since glycerin and water play well together, it is easy to see the benefits of taking that bar of cold processed soap into the shower. A wet body + glycerin is a good thing for skin since the glycerin works to hold moisture that might otherwise evaporate.

The glycerin remains in the soap simply because we do not remove it. Commercial soaps typically remove the glycerin for shelf stability, which removes the naturally moisturizing properties of a cold-processed, natural soap.

So, why is our soap better than commercial soap?

A properly formulated soap will be an effective cleanser that doesn’t strip away all the oil, leaving you in desperate need of immediate re-hydration.

Let’s check out a couple of basic reasons for using cold-processed soap.

- First, the glycerin is retained in our cold processed soap.

- Second, we leave a little extra oil in the bar. It is a small percentage, but enough to work with the glycerin and offer some outer layer skin protection.

- Third, we use only what ingredients are needed to get the job done. Our ingredient list may look pleasantly boring when compared to commercial soap.

The misconceptions of using lye

Speaking of chemicals, I need to bring up the NaOH (lye) issue here. Without lye, you have no solid bar soap. It is necessary for the saponification process. Period. That’s it, gotta have it. We have had people turn away from our soap because we use lye.

Evidently they are going under the assumption that because they see soap that does not list lye as an ingredient, it is not needed. Technically speaking, lye is actually not present in a correctly formulated bar of soap, but it was necessary to *make* the soap.

Homemade lye is likely the cause for disdain at the mention of lye because of grandma’s homemade lye soap. Lye can be made with water and hardwood ash but the purity will vary. Not knowing the actual strength of the NaOH could throw off the proper ratios of fats/oils to lye. Fortunately, our lye has a published purity so we can accurately calculate a proper formulation.

“Glycerin soap” confusion

“Glycerin Soap” might be the reason people are confused about the lye issue. Glycerin soap, also called “Melt and Pour” is sold by crafters, and appears to be more “natural” to the consumer. It is not.

Melt and pour is a block of soap that has added ingredients to make it readily able to melt and pour into molds. So, yes, the crafter can claim they did not put lye in their soap (but it was used to make the product in the beginning). It also contains various unnecessary additives to make it opaque, as well as other ingredients for eye-catching appeal.

A hard look at some commercial soaps

Now let’s take a look at the “commercial” type soap. For example, a bar of Dial soap. One additive in the Dial which you would never find in a hand crafted soap is triclocarban. This is an anti-bacterial agent and is completely unnecessary and even harmful.

Next, let’s check out the Olay Sensitive Beauty Bar soap. For starters, on the company website, it is labeled as “unscented” but the ingredient list includes “fragrance/parfum”. Now, that could just be an error on the website. Or maybe unscented does not mean unscented like it does in my world. And check this out: the second ingredient is “paraffin”. Paraffin is a petroleum-derived product. Oddly enough, there is a food-grade paraffin used in the food industry. I guess it has been determined if we can ingest it, we can bathe with it. I am clueless as to the need for paraffin over a plant-based oil.

Titanium dioxide is another popular additive with the commercial soap. There has been controversy brewing around this ingredient for some time. Its primary purpose is to make a product appear lighter than it naturally would be. It is not used in any of our products and I tend to avoid it in personal purchases when there is a choice.

So, this is what you find with commercial soap – a product that will get you clean, but at what cost?

I am not exactly sure why a simple bar of soap has to be processed so harshly to the point of removing the glycerin. If I had to speculate, it would be shelf stability. With the glycerin removed, the product can sit in a box and not draw humidity from the air and cause damp packaging. It can also be wrapped tight and not have internal moisture issues. Also, I would be surprised to find any extra oil in the commercial soap.

The oil is great for your skin but again, not so great for long-term shelving.

Is cold-processed soap worth the trouble?

Cold-processed soap is high-maintenance in these regards. You want the soap bar to have some breathing room. The soap will contain some excess oil, a bit of water, and glycerin. It will sweat under high-humidity conditions. The fresh cut bars have to sit on a drying rack for almost a month to allow excess moisture to escape.

This is the nature of cold-processed soap and we think it’s worth it.

How we make our cold-processed goat milk soap

I have been concocting regular water and lye soap since the 1990’s and began experimenting with milk soap in 2010. Testing revealed that the goat milk soap left the person feeling less dry after a shower. You know the dry where your skin feels drawn tight, like a cotton shirt that just came out of a hot dryer? The goat milk soap gives a good, clean feel without that dry, tight feeling.

Our water-based soap was close to the goat-milk experience, but the milk bar gave a superior experience. This, plus the fact that we have dairy goats, put me on a journey to learn the mechanics and chemistry of milk soap. I was hoping it would be as simple as substituting milk for water in the lye solution. What I found out rather quickly was that making milk soap has a steep learning curve.

Milk contains sugars, fats, protein, vitamins, minerals and more. If no milk is added to a soap mixture at any stage, the procedure is rather straight forward, and involves high temperatures at several stages.

When mixing milk with the lye, the heat becomes problematic.

I found it very important to take steps to keep the solution cool, below 100° F. Regardless of how low the temperatures are kept, the milk and lye solution will always turn a shade of yellow. If the temperatures rise much above 100° F, the solution will start becoming orange and have an ammonia smell. The smell will eventually dissipate but to avoid compromising the integrity of the finished product, we feel it best to toss the mixture if this occurs.

Now, even after the soap is poured into a mold, the milk soap runs the risk of overheating within the first 6 hours of mixing. Overheated soap may crack and be much darker than normal. The key to a nice bar of milk soap is to keep the temperatures under control.

The vitamin benefits of using goat milk in soap

For all of its complications, using goat milk has a few great things going for it, like built-in vitamins. Some beauty creams and lotions are fortified with synthetic vitamin A because it’s recognized for skin cell growth. There are also vitamins C, D, and several types of B, which may be beneficial when applied to and absorbed into the skin. It also contains minerals like selenium, which may help against sun damage.

Goat’s milk also contains alpha hydroxy acid and lactic acid. These are not chemical additives, but are naturally occurring in goat milk.

We all know that we need to exfoliate in order to have healthy skin. Well, alpha hydroxy and lactic acid are a gentle way to exfoliate and get a smooth, healthy look without harsh scrubbing or chemical treatments.

Beth here again… Whew! That was a LOT of information, but I hope you found it as fascinating as I did.

I want to thank Ricky for taking the time to share all of that with us today. Before I wrap this post up, I want to share my own assessment of using the Taproot Farms Co. goat milk soap.

This past year has been all about diving deep into my skincare routine and what I want that to look like from a natural, non-toxic perspective.

I’ve been using Taproot’s goat milk soap for many months now, and I’ve been savouring every bit of it. The soap is unbelievably luxurious, produces a beautiful, rich lather, and smells incredible.

It’s honestly a highlight in my day to be able to use such carefully made, hand-crafted, natural products that I know are tenderly nourishing my skin instead of harming it.

It feels like such self-indulgent luxury that I hoard it and carefully tend my bars so that we don’t waste a single bit!

Of course, I’ve known for a long time how deliciously wonderful I find it to indulge in a rich lather of hand-crafted soap, but now I know the why behind it all. And that just makes me happy.

Are you a fan of cold-processed goat milk soap? What kind of soap do you use?

This conversation was sponsored by Taproot Farms Co. because I wanted to dig deep into the science of soap, they were the perfect company to help me understand it! Their soap is a million percent awesome, and I use it on a daily basis in my home. I only work with companies that jive with my values, and my opinions in sponsored posts are always completely genuine and real.

Levi

Love the article but I’m confused by the sentence “If the soap is clear or opaque, it’s probably melt and pour.” I’m assuming you accidentally used the wrong word, happens to me all the time! I’m just wondering which one is correct. Is the melt and pour clear/translucent, or is it opaque/non-translucent?

Kadija Williams

Love love love!!!! This was so informative and very detailed. I’m a young gal in the military and wanted more information on soaps because I have a desire to eventually start my own small online business. This was very helpful and gave me much hope for making soap.

Lois Clark

I found this article so informative! I have been making soap for about 3 years and have noticed a total change in my skin. I no longer have dry skin in the winter. I totally agree that the simple ingredients are best. What do you use for scenting your soaps or do you make unscented?

Gayle

Hi!

In your article, you state “if soap is clear or opaque, it is probably a melt and pour.” What else can it be? It will either be clear or it will be opaque, no?

Daniel

Good catch Gayle. I think some people misunderstand the word ‘opaque’ to mean ‘clear’.

Ethel

Your information about melt and pour is false. SFIC Melt and pour comes in all natural ingredients with no ‘added ingredients’ to make it melt. It is better than commercially made bars AND I don’t have to bother with lye. I know exactly what is in my soap and I have MORE fun using molds. To each his own with soapmaking, but don’t put down another great soap with false claims just to make your preferred method seem better.

Nadia

Hi Beth! Thanks for this interesting article! About the reason glycerin is removed from the soap, it’s because companies make a LOT of money selling it to pharmacies or to the government for an example. Then, glycerin costumers can make nitroglycerin with it. And the only place to find glycerin is in soaps. It is not good for us to use the glycerin deprived soaps because, without glycerin, no natural agent is covering our skin until the oils of our body form on the surface of our skin. Some company will add a little bit (maybe up to 25%) of glycerin to the list of ingredients but that’s because they firstly removed it all. I was told that the alcool in perfumes will affect the quality of the glycerin so you want to stick with essential oils if you want to add a fragrance to your soap. I have been explained all this from an employe of a soapery.

Milly

Really good information. I would like to know why a homemade soap creates white spots that look like fungus. What happened during the process that caused it. I’ll be happy to know the why. Thanks.

Terry Lawrie

Hi Beth, thanks for sharing this information. I live in Italy and have a small olive grove of 100 trees and I produce my own extra virgin olive oil. This year I had some left that was losing it’s pungent peppery taste so rather than throw it away I started making olive oil soap, it’s incredible but some people have concerns about the sodium hydroxide. This post explains things very well, would you mind if I link this post to my Facebook page and website one they are published?

Thanks Terry

Beth

Glad you enjoyed the post. Links are always welcome!

Janee

Another great post. Thanks for so much great info. So far I’ve gone natural with most of my body care products and soap is on my list of someday things to make. I’ve been waiting until we can have our own goats so its good to know goat milk soap is ticky and I will have to do more research before trying that. Right now I’ve been experimenting with using Kirklands Castile soap to make body wash but eventually I want to make my own bar soap. I may have to start with coconut oil until we can get goats. Lots of recipe’s out there to try.

MamaV

We don’t use much soap at all around here, but when we do I try to use cold processed soap without added ingredients. I would love to make my own, but can’t really find the time 😉

Maybe I will try some taproot farms soap when my other bar finally runs out 😉